Energy Transitions

Nuclear energy

What do India’s nuclear power ambitions mean for its energy future?

1 September 2025

Glimpses of the Unit III dome and the project site of Tarapur Atomic Power Project (TAPP) near Mumbai. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

India has set a short-term goal to increase its nuclear power capacity to 22.5 GW by 2032, and a long-term target ambition to reach 100 GW by 2047, as part of its broader strategy to achieve energy independence. In the Budget 2025-26, the Government of India introduced a Nuclear Energy Mission and allocated INR 20,000 crores to develop at least five domestically designed and operational small modular reactors (SMRs) by 2033. These ambitions represent a strategic shift, positioning atomic energy as an integral component of India’s 21st century energy portfolio and a vital driver of economic growth towards realising Viksit Bharat (Developed India) by 2047.

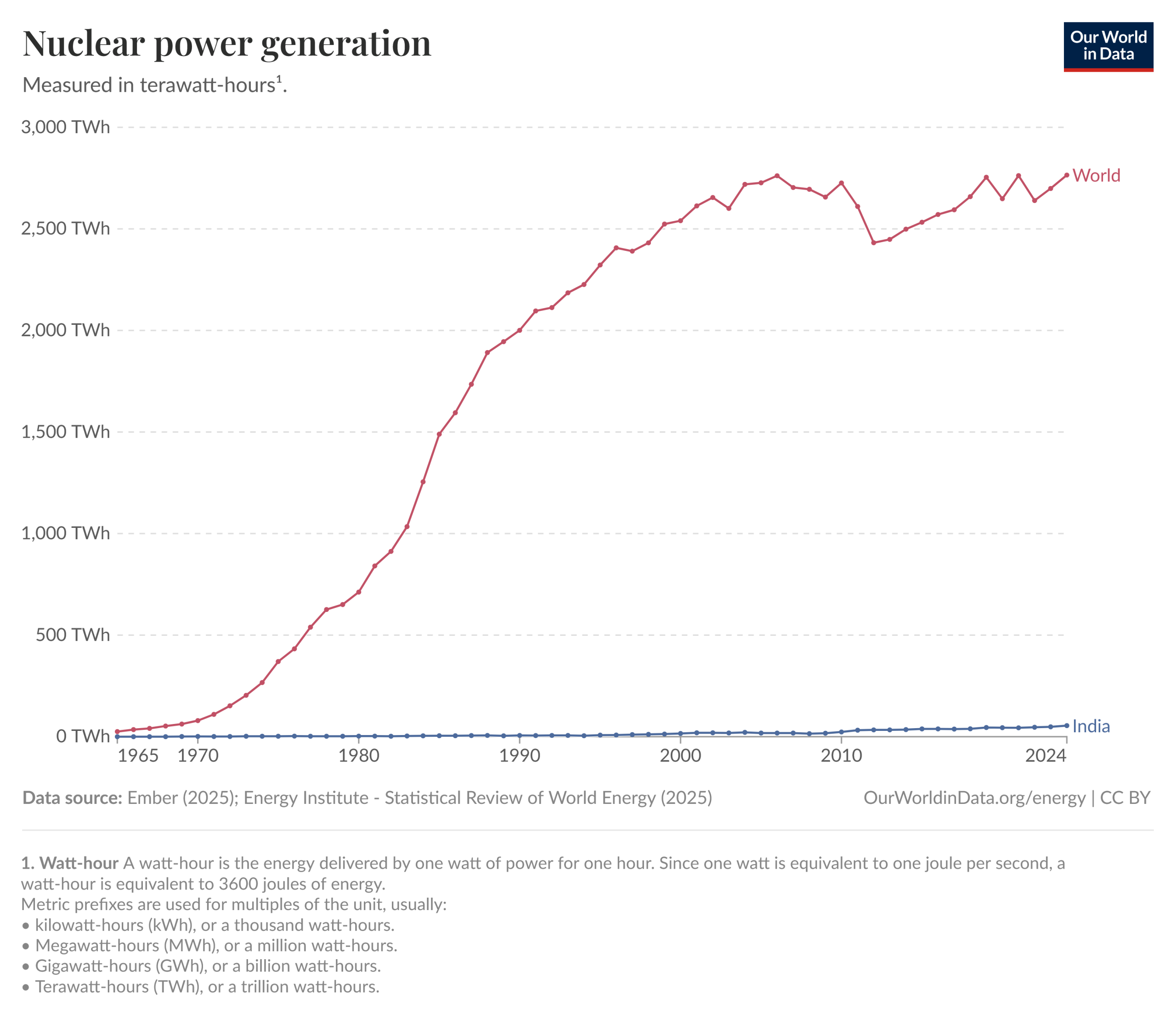

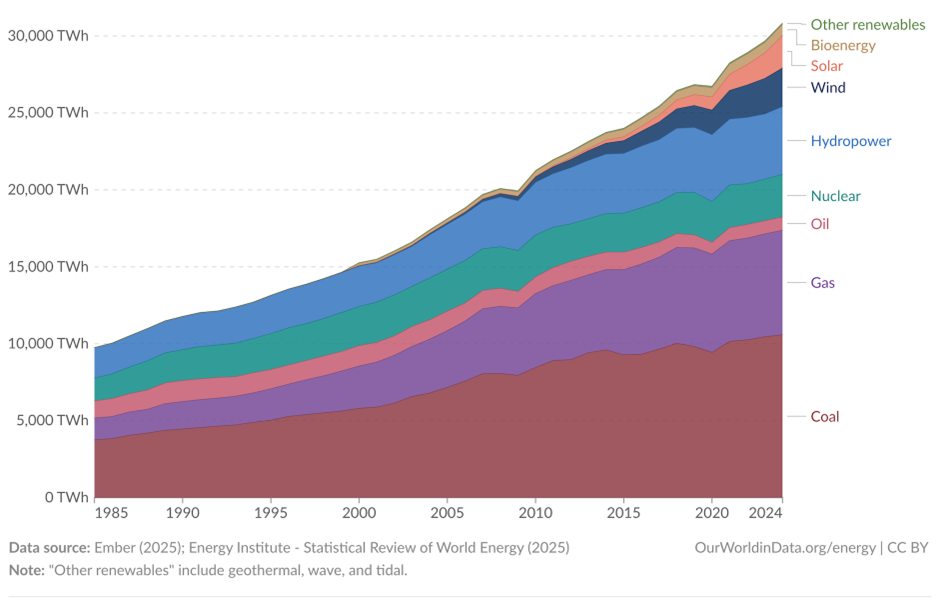

Nuclear energy, a symbol of scientific prowess in the mid-20th century, has been an important part of the global electricity mix for the last five decades. It accounted for about one-fifth of global electricity generation in the 1990s, subsequently plateaued, and currently accounts for just below one-tenth of global electricity (see Fig. 1). Yet, it is the second largest source of clean energy after hydropower (see Fig. 2).

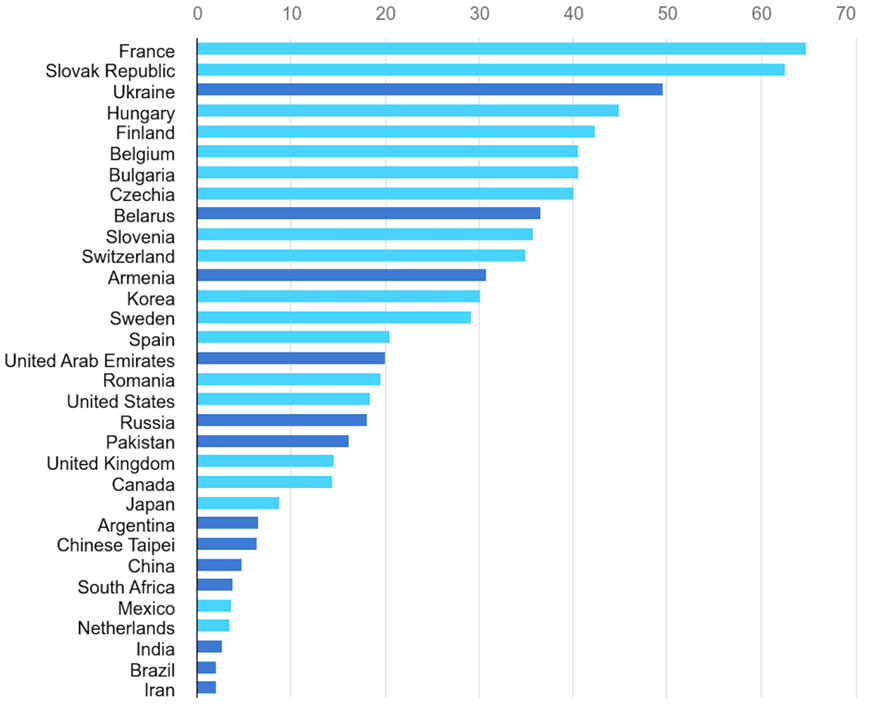

Despite a long history of initiatives, ambitious promises, and consistent public spendings, nuclear power currently accounts for less than 2% of India’s total electricity capacity and about 3% of overall generation – a meagre share compared to other major economies (see Fig. 3). Achieving the 2047 targets will require a 12-fold increase in installed capacity. What drives the renewed push for nuclear energy? How does this align with India’s energy transition goals? What are the challenges to realising this ambition?

The return of nuclear power

Lately, there has been a renewed global momentum behind nuclear power. In COP28 (2023), 25 countries (with about two-third of global nuclear energy capacity) signed a declaration pledging to triple nuclear energy capacity globally by 2050 to limit global warming. Subsequently, the United States has unveiled a plan to add 200 GW nuclear capacity by 2050 and Sweden has launched a roadmap for 25 GW additional nuclear capacity by 2035. Even countries that have an uneasy past with nuclear energy, such as Japan and Germany, appear to be pivoting back. The European Union green taxonomy has labelled nuclear power as green – environmentally sustainable energy source – as long as it is used to replace dirtier fossil fuels such as coal and oil. The World Bank has recently put an end to the ban on funding nuclear power.

The first major push for nuclear power occurred during an energy supply crisis – the oil crises of the 1970s. After half a century, the resurgence of interest in nuclear power is largely driven by exceptional growth in energy demand alongside increasing pressures to decarbonise energy consumption. Global electricity demand is rising fast, not only for conventional end-uses (lighting and thermal comfort) and energy switch (transport electrification), but also for new demands from data centres, cryptocurrency, and artificial intelligence. The earlier assumption about the global energy demand trajectory – that developed economies have already peaked energy demand and can taper their energy consumption for climate action – is proving wrong. Additionally, the escalation of geopolitical conflicts, exemplified by the Ukraine-Russia conflict and its impact on the global energy supply chain, has re-emphasised the importance of national energy security as a priority. Consequently, there is an emerging global policy shift that puts national energy security first, making space for nuclear power as a key solution for energy security and decarbonisation.

India’s current nuclear ambition might be influenced by the global hype, but it is not abrupt. While championing a rapid global transition to renewable energy (RE), India’s own energy transition goals have always been pursued within the broader framework of its domestic energy security, with an all-of-the-above approach to capacity addition. Responding to the demand surge in recent years and economic growth aspirations, India is doubling down on RE, hydro, coal, and nuclear simultaneously.

India’s current nuclear ambition represents a significant shift in approach from its previously protected and public-funded nuclear programme. First, the Atomic Energy Act was amended to enable Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) to form joint ventures (JVs) with other public sector undertakings (PSUs) for setting up nuclear power plants. The expectation is that the PSU partner will bring investible surplus capital, while the NPCIL brings nuclear expertise and keeps a controlling stake. NPCIL has launched JVs with Indian Oil Corporation, NALCO, and NTPC. Second, the government is planning to amend the laws to open nuclear energy to private and foreign players. The private sector is expected to advance technological upgrades, fill the finance gap, and address time and cost overrun challenges, and thus, make nuclear power cost competitive. Third, keeping with the global trend, India is also betting heavily on SMRs (16 MW – 300 MW size) through the Nuclear Energy Mission. SMRs promise to have a short gestation period, better upfront capital cost affordability, and fit for captive use and co-generation for industrial decarbonisation. Finally, India seeks to boost domestic capacity by designing indigenous reactors to avoid risks of import dependency.

India’s current nuclear promises are based on two recent studies. An IIM Ahmedabad study (supported by the Principal Scientific Advisor to the Government of India and NPCIL) suggests that an energy mix with half of the electricity generated from nuclear power is the most likely scenario to achieve the lowest levelised cost of electricity in 2070, while meeting India’s net-zero targets. Another study by Vivekananda International Foundation makes similar projections for nuclear energy. Both studies emphasise the promise of nuclear power to be the most cost-effective and low-carbon option for baseload generation that can power India’s ambitious economic growth trajectory.

How does nuclear power fit into India’s energy mix?

India faces the challenge of meeting growing energy demand while reducing its reliance on fossil fuels to achieve net-zero emissions. Is nuclear power a suitable alternative to reduce India’s dependency on coal? Will nuclear power complement India’s ambitious plan for RE or compete with it? To answer these questions, we need to understand the comparative advantages of nuclear and RE as clean energy options.

1. Dispatchability: RE generation is intermittent, and requires complementary energy storage to be dispatchable — where output can be adjusted to meet variable demand. Planning for seasonal variations in RE generation and exposure to extreme weather events requires oversizing both RE and storage capacity. The practicality of large-scale storage solutions required for a complete shift to RE are currently unclear.

Nuclear power is advocated as an alternative clean and dispatchable energy source. Though nuclear power plants are often designed to run at full capacity to meet baseload, they can also be designed to ramp up or down at a rate of 3 to 4% of plant capacity per minute.

2. Cost competitiveness: Cost projections are optimistic for both RE-plus-storage and nuclear power. Solar-plus-storage bids have come at INR 3.10 – 3.50/kWh (with limited storage), and 100% reliability is estimated to cost below INR 6/kWh. RE-plus-storage price is on a declining trend.

The IIM Ahmedabad study projects nuclear power cost at INR 2.76 – 3.60/kWh (at 2020 constant price) in 2070 (Average tariff of nuclear power in India was INR 3.83/kWh in 2023-24.). Nuclear projects are often affected by time and cost overruns, resulting in high tariffs. Advocates argue that nuclear power could be made cost competitive by managing indirect costs during the construction period. Critics point out uncertainties in predicting future cost of nuclear power.

3. Modularity: RE technology is modular, which allows deployment at a faster pace and varied scale. Traditional nuclear power has been very large, with higher cost and geographical requirements. SMRs are being designed to bring modularity through factory fabrication, which in turn will address time and cost overruns, and unlock nuclear power from large capital requirements. While RE, particularly solar, is an option for small consumers (household, commercial and farm use), SMRs, if successful, could fit for captive use by energy intensive industries.

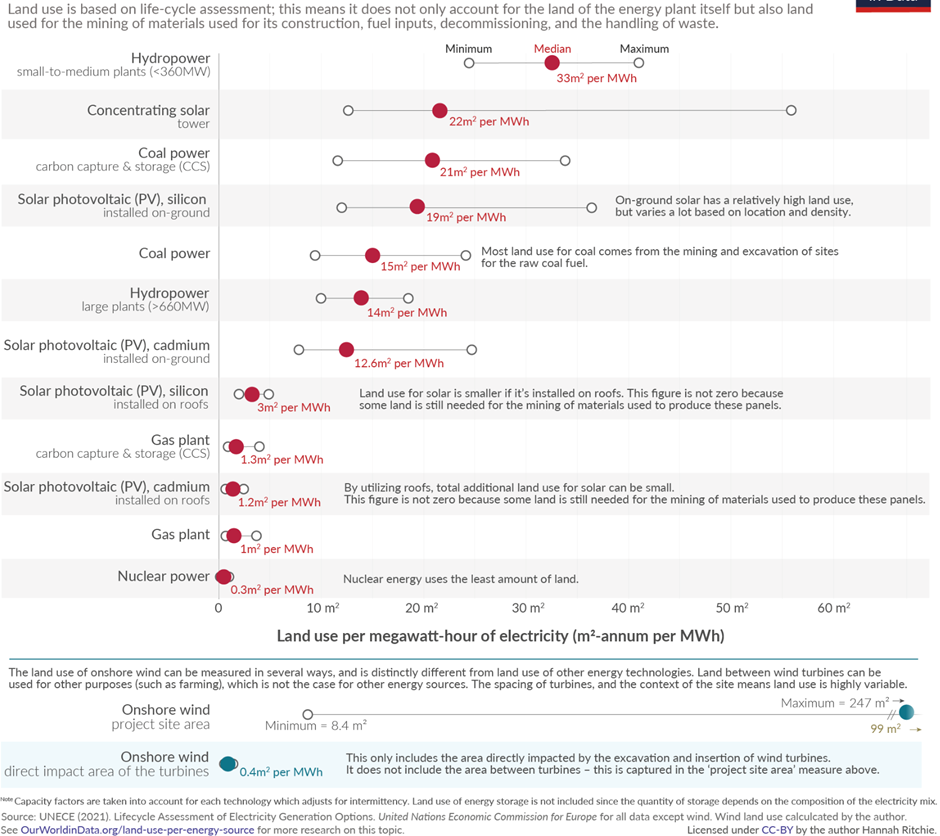

4. Land intensity: As RE projects are land intensive, land acquisition and use are emerging as concerns in RE transition. India is already experiencing early land conflicts in case of RE projects. Even though nuclear power has specific geographical requirements, it is still considered the most land efficient among various energy technologies (see Fig. 4). SMRs used for captive use may further reduce land requirement.

5. Safety: Safety risks associated with nuclear power have been a major reason for public resistance and have caused slowdown in capacity expansion in the last two decades. Radiation leaks and exposure to natural disasters have led to nuclear accidents in the past. The risks are even higher for SMRs, as they tend to produce more voluminous and radioactive wastes. Lack of proper waste disposal infrastructure and robust regulatory safeguards heightens the risks.

RE waste also has potential toxic impacts on human and environmental health. However, studies estimate that RE (wind and solar) waste will still be less voluminous compared to coal and other wastes in 2050. A substantial part of RE waste could potentially be recycled. Rising concerns over RE waste and scarcity of materials and critical minerals are likely to boost the imperative for circularity in the RE supply chain.

Key challenges to realise India’s nuclear ambition

Nuclear power promises to be a complementary option for India’s 21st century energy portfolio. While its dispatchability and projected cost-competitiveness makes it an option for coal substitutions, potential for faster ramp-up and ramp-down makes it a complement to variable RE. However, nuclear power has to pass many tests before it can deliver on its potential.

– Social legitimacy: Risk perceptions associated with nuclear radiation have been a barrier to nuclear power projects in India and globally. The first test would be to gain social legitimacy through effective regulatory and enforcement mechanisms for secure waste management, better risk management, and public awareness.

– Finance & private sector participation: Nuclear power requires larger capital investment than its alternatives. India’s nuclear ambitions rely on the effective mobilisation of capital, which would be consequential to its cost competitiveness and pace of development. The scale of investment requires private capital and private sector participation, which could be unlocked through enabling regulations, policy certainty and risk sharing. The Government of India is already planning necessary legislative reforms and the private sector has shown keen interest.

– Domestic manufacturing: Nuclear power expansion requires heavy engineering manufacturing capacity. While this is a constraint with limited capacity in India (dominated by players like Larsen & Toubro, Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd. and Bharat Forge Ltd.), it is also an opportunity to boost domestic capacity and reduce dependency on global equipment supply chains.

– Fuel supply security: Expanding nuclear capacity requires a strategic uranium fuel reserve to maintain supply chain resilience. India relies on Kazakhstan and Russia for additional uranium fuel due to insufficient domestic supply. Its historical three phase programme has always been on a path towards making thorium reactors viable, thereby utilising a fuel source which is available in abundance in India. While thorium reactors are yet to be deployed commercially, China built the world’s first operational (experimental) thorium reactor in April 2025. India’s prototype fast breeder reactor in Kalpakkam is yet to be commissioned.

– SMRs: SMRs are a promising option for flexible electricity generation and specific end-uses. Globally, there are more than 80 SMR designs and concepts at various developmental stages. India is also investing in SMR technology. The maturity of this technology will have significant implications for India’s nuclear development.

– Exposure to climate hazards: Existing and new nuclear power plants are susceptible to rising climate-related extreme weather events, including heatwaves, droughts, sea-level rise, altered precipitation patterns, and storms. In 2025, several nuclear power plants in Europe reduced operations or temporarily shut down due to heatwaves. The cooling water reached temperatures that were not suitable for effective cooling processes. Adaptation strategies and enhanced safety measures could help address these risks, though they may require additional costs and time.

If India can address these challenges, nuclear power may help reduce its reliance on coal. However, it is not a substitute for its RE pursuits. India has to be mindful that capital requirements for nuclear energy do not cannibalise RE investments. Rather, as nuclear power gestation period is longer, India must double down on RE deployment to meet the interim demands. Besides, India has to plan carefully for potential geopolitical instabilities (like USA’s attack on Iran’s nuclear sites) and its implications for pace of development, fuel supply security, and thus, for its energy independence goal. Overlooking these challenges may render nuclear power an expensive and hazardous distraction in the 21st century energy transition.