Background

Heatwaves are expected to increase with climate change, posing a significant threat to population health. In India, with the world’s largest population, heatwaves occur annually but have not been comprehensively studied. Accordingly, we evaluated the association between heatwaves and all-cause mortality and quantifying the attributable mortality fraction in India.

Methods

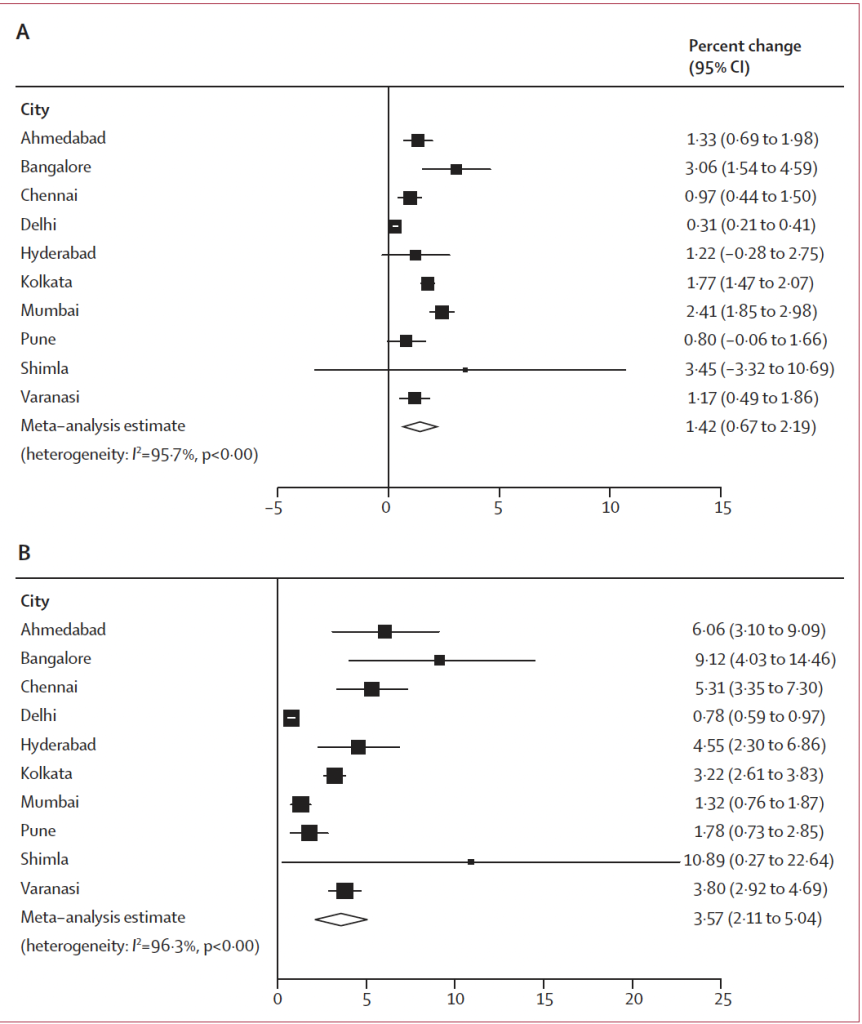

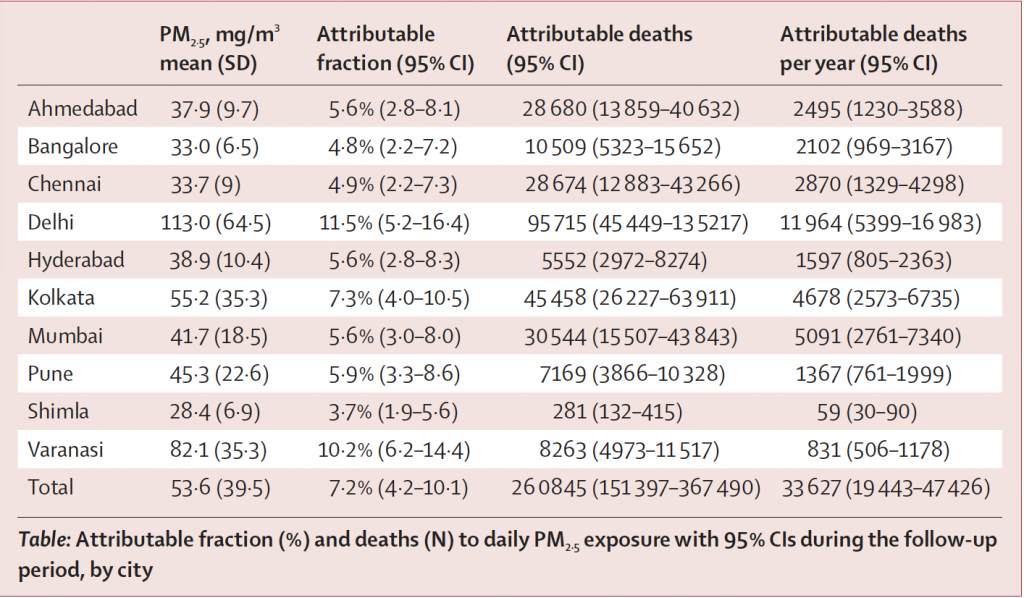

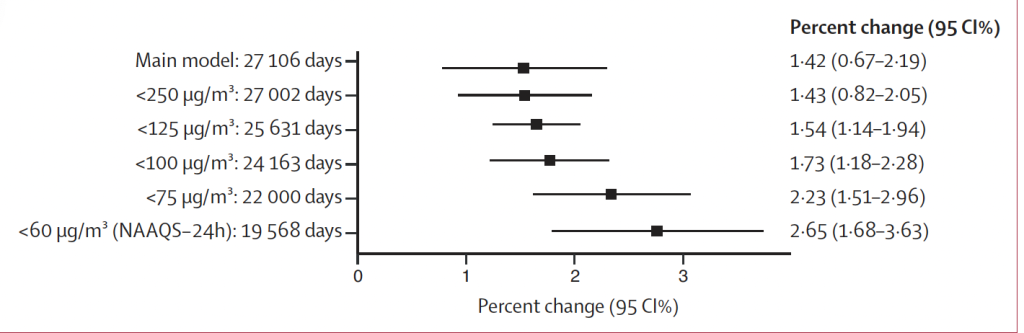

We obtained all-cause mortality counts for ten cities in India (2008–2019) and estimated daily mean temperatures from satellite data. Our main extreme heatwave was defined as two-consecutive days with an intensity above the 97th annual percentile. We estimated city-specific heatwave associations through generalised additive Poisson regression models, and meta-analysed the associations. We reported effects as the percentage change in daily mortality, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), comparing heatwave vs non-heatwave days. We further evaluated heatwaves using different percentiles (95th, 97th, 99th) for one, two, three and five-consecutive days. We also evaluated the influence of heatwave duration, intensity and timing in the summer season on heatwave mortality, and estimated the number of heatwave-related deaths.

Findings

Among ∼ 3.6 million deaths, we observed that temperatures above 97th percentile for 2-consecutive days was associated with a 14.7 % (95 %CI, 10.3; 19.3) increase in daily mortality. Alternative heatwave definitions with higher percentiles and longer duration resulted in stronger relative risks. Furthermore, we observed stronger associations between heatwaves and mortality with higher heatwave intensity. We estimated that around 1116 deaths annually (95 %CI, 861; 1361) were attributed to heatwaves. Shorter and less intense definitions of heatwaves resulted in a higher estimated burden of heatwave-related deaths.

Conclusions

We found strong evidence of heatwave impacts on daily mortality. Longer and more intense heatwaves were linked to an increased mortality risk, however, resulted in a lower burden of heatwave-related deaths. Both definitions and the burden associated with each heatwave definition should be incorporated into planning and decision-making processes for policymakers.

Read more