Adaptation and Resilience

Extreme heat

Hot Takes, Cold Action: How Heat is Misplaced Within India’s Bureaucracy

4 July 2025

An Indian man sitting outside the grungy wall of a building fitted with air conditioners in Goa. Source: iStock

Extreme heat is no longer a distant threat. Over the past few years, it has claimed lives, destroyed crops, disrupted governance, and pushed India’s systems to the brink. In 2022, intense heatwaves devastated wheat crops, prompting an export ban. A year later, over 600 people suffered heatstroke at a state award ceremony in Khargar; 12 died. And in 2024, at least 33 people, including election officials, died from suspected heatstroke during the Lok Sabha elections.

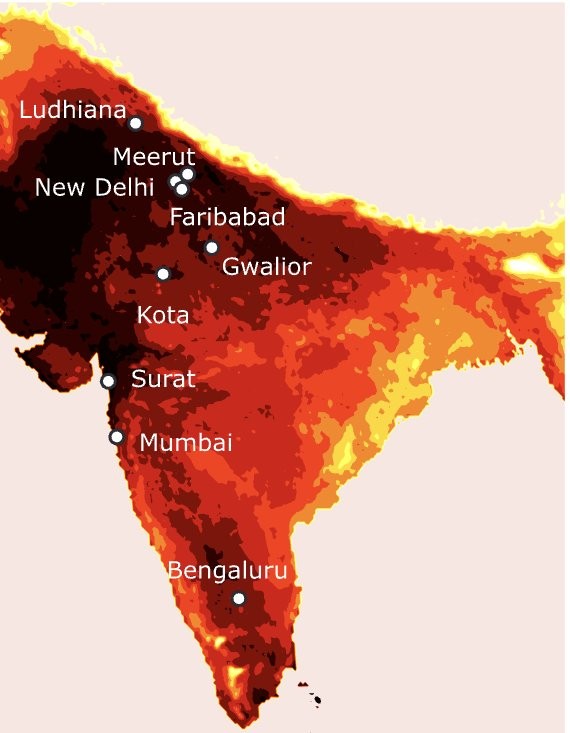

This year is no exception. February 2025 was India’s hottest in 125 years, with many states breaching 40°C. Reports of heat-related deaths came in from Telangana, Gujarat, Punjab, and Odisha. Yet, despite these rising impacts, extreme heat continues to be treated by the bureaucracy as a seasonal, static, and short-term risk. In reality, heat is complex, pervasive, and deeply unequal in how it impacts different communities and sectors.

As part of our recent study on the implementation of heat resilience measures in nine Indian cities, we spoke to 88 officials across disaster management, health, urban planning, and labour departments. We found a fragmented and often inadequate understanding of heat as a policy issue which directly shaped actions and responses.

This blog draws on those conversations. It unpacks why heat remains overlooked by many parts of the Indian state, and what it will take to shift that mindset.

Bureaucracy misunderstands the threat of heat

The way bureaucracy responds to heat as a policy issue is fundamentally shaped by its understanding of the threat. This understanding – or often – misunderstanding, is influenced by two key phenomena: the rapidly changing nature of extreme heat, and the diverse, pervasive ways it impacts the population.

India has historically been a hot climatic zone, making heat a familiar presence. However, the extreme heat we face today is unprecedented, escalating at a much faster pace with threatening increases in heatwave days, humid heat days, and warm nights. This rapidly evolving nature of heat is a far more serious policy challenge than it is currently understood to be. Given the alarming rate of change, it becomes crucial for the bureaucracy to internalise this dynamic threat and adapt its response mechanisms accordingly.

Heat also impacts every sector and individual differently. Its impacts differ based on factors like the nature of work, built environment, and physiological conditions of an individual. Impacts spread from the workplace, affecting productivity and wage loss, to homes and public spaces, often hitting vulnerable, invisible groups the hardest. Many of these second and third-order effects are difficult to see and often go overlooked.

This inadequate understanding of heat’s complex, pervasive, and evolving nature shapes how the Indian bureaucracy currently responds to it: as a static, seasonal, and contained risk. As a result, heat actions are skewed towards short term reactionary measures, rather than long-term solutions.

During our fieldwork, we observed this misperception in three significant ways: first, in how heat is contained within bureaucratic memory; second, in how heat actions are currently implemented at local levels; and third, in how the state understands and records the health impacts of heat.

1. Bureaucratic memory around heat is seasonal

Heatwaves are still not fully understood by our systems, both in form and intensity, rendering them largely invisible. Heat seasons are often seen to last specifically from April to July, without much room for recognising their severity and preparing for the threat beyond these months. One official summed up this approach by remarking, “Now heat is past and we need to move on,” explaining how heat was no longer seen as a threat, with their focus shifting to the next seasonal issue – the monsoons.

This seasonal outlook towards extreme heat also means that even the most severe episodes of heat get treated as isolated events, not as signals of a growing, structural threat. This is partially due to a lack of technical capacity to understand the changing nature of the threat, coupled with shortage of staff. For an already overburdened local bureaucrat, a sentiment echoed by one who said, “There is so much work in the existing things which we have to do, let alone doing anything separately on our own,” there’s almost no institutional room for heat to be addressed. The result is a governance cycle defined by reaction rather than preparedness, falling short of being able to build any form of long-term adaptive capacity.

2. Heat actions lack local ownership and heavily depend on top down guidelines.

Effective heat actions must be locally driven, given their hyperlocal impact. However, current heat governance is heavily influenced by rapid response guidelines from state and central departments. We found this in response to questions on agenda-setting, as one official remarked, “We are waiting for guidelines from above.”

This strong dependence on national or state directives, from ‘dos and don’ts’ and awareness materials to specific funding, severely limits local ownership in solving for heat. As another official expressed, “It’s simply not on the agenda. If the central government issues directives or even encourages public awareness, then something will happen.“

These rapid response guidelines, while immediate, are filling a gap for a quick fix and a short time. They tend to be issued annually, acting as a temporary measure rather than fostering long-term, integrated solutions. However, their short term nature and a one-size fits all approach makes them an ineffective measure to build long-term adaptive capacity for heat, failing to protect the most vulnerable groups and address specific, evolving needs on the ground.

3. Invisibility of heat death reporting

The true human cost of heatwaves in India often remains obscured, primarily due to significant underreporting of heat-related deaths. While heatwaves are the deadliest natural hazard in Indian cities, official figures paint an incomplete picture. For instance, in 2024, India experienced a staggering 536 heatwave days (the cumulative total of heatwave days across all regions of India), the highest in 14 years, according to the India Meteorological Department. The official data reported only 41,789 suspected heatstroke cases and 143 heat-related deaths, a figure expected to be severely underreported.

This is partly due to the very nature of heat and how it presents during medical evaluations, from routine check-ups to emergency situations. Heat usually rides on – or hides behind – other medical conditions such as heart failure, respiratory distress, kidney dysfunction, or exacerbated pre-existing illnesses. This invisibility of heat as a ‘trigger’ often gets masked by the more immediate, observable physiological failures. It is, therefore, very hard to accurately attribute a death solely to heat, making it challenging for medical professionals to list it as the primary cause of death on certificates.

Despite the challenges in accurately attributing deaths, past experiences with high-mortality heatwave events have, paradoxically, played a crucial role in shaping future actions on the ground. As one official revealed, “Deaths this year have helped provide the services. This has helped create pressure. First time I have heard hospitals created heat wards.”

With low estimates of deaths in the official records, media coverage of heatwave deaths also often serves as a catalyst for bureaucratic action. Furthermore, an official highlighted the role of the media, explaining, “If anyone suffers from the heat, the media covers it extensively. Bureaucrats are keen to avoid negative publicity, so even if some of the actions seem superficial, they do get implemented effectively.” This underscores how the visibility of public health impacts, whether through media or, ideally, accurate official data, can push government bodies to address the issue.

How we see heat matters

The prevailing view of heat as a slow, silent threat has led to deep bureaucratic underestimation of its urgency. In our study, we found that heat actions in India are currently driven by short-term measures directly linked with how bureaucracy perceives heat, often missing out on major long term measures that could help build community resilience and enhance adaptive capacity. In cases where we found long-term actions being implemented, they were poorly targeted.

While national guidelines and central mandates have helped make heat visible as a public health issue within the bureaucracy, a comprehensive approach requires a fundamental shift in perception. This starts with building capacity both within institutions and the bureaucracy to assess, track, and respond to this evolving threat. It also means looking beyond traditional disaster management and integrating sectors such as labour and urban planning into heat discussions. Solutions must account for the ripple effects of heat: school closures, reduced work hours, infrastructure stress, agricultural losses, and more.

Finally, effective heat action needs to stem from the ground, locally owned by those directly affected by it. This necessitates targeted vulnerability mapping and active community involvement, as heat will impact those most who are already at the brink of survival. Dedicated funding channels, coupled with active community engagement and the involvement of stakeholders most impacted by heat in their daily lives, are crucial. This approach ensures that interventions go beyond temporary relief, tackling the fundamental sources of vulnerability, such as dangerous employment or living conditions, for lasting resilience. Only then can heat resilience become an embedded, continuous part of planning, policy, and decision-making.

Tamanna Dalal and Aditya Valiathan Pillai contributed to this article.